Purpose of the flight and payload description

Stratoscope was the first unmanned balloon-borne telescope flown for astronomical research. The project was under the direction of Professor Martin Schwarzschild of the Princeton University Observatory, and sponsored by the United States Office of Naval Research. The United States Air Force contributed funds for the development of the pointing control system. The objective of the project was to obtain images of the solar granulation with an unprecedent resolution and detail.

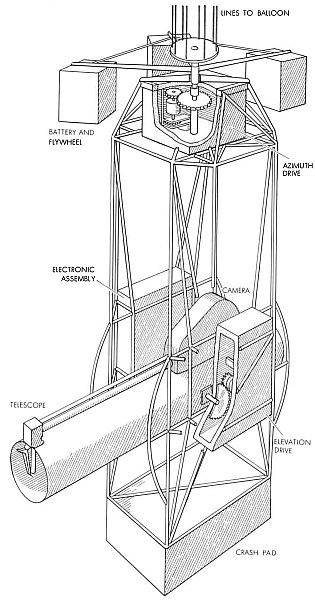

A basic scheme of the system can be seen at left (click to enlarge). The telescope which was designed and constructed by the Perkin-Elmer Corporation, had an eight-foot long tube, at one end of which was a parabolic quartz mirror 12 inches in diameter. At the other end of the tube were a plane mirror and a prism that reflected the light gathered by the parabolic mirror back along a path above the tube of the telescope into a 35-millimeter motion-picture camera. A lens in the light path enlargeed the image presented by the primary mirror to the size of an image that would be produced by a 200-foot telescope. At this magnification each frame of the 35-millimeter film covered a rectangle about 50,000 by 35,000 miles on the surface of the sun. Exposures were made at a rate of one per second, each lasting a thousandth of a second.

The guiding mechanism for the telescope was designed and built by the Research Service Laboratories of the University of Colorado. The telescope tube was mounted in a gimbal structure about 12 feet high on axes which permitted motion in elevation and azimuth. Small photosensitive cells searched out the sun and controlled the electric motors that moved the telescope. The telescope was aimed in azimuth by rotating the gimbal structure against the reaction of a 175-pound flywheel, and in elevation by rotating the tube against the reaction of the whole framework. At the top of the figure at left can be seen the six four-volt automobile batteries distributed around the circumference which served as the weight for the flywheel and also as power to drive the pointing motors, the electronic controls, and the camera.

In flight the top part of the instrument was attached to a 90 feet long cargo parachute through a bearing located immediately above the flywheel, and the top part of the parachute was in turn attached to the bottom of the balloon. After the film in the camera was exhausted, a preset timer stowed the telescope vertically within the frame and cut down the parachute away from the balloon. In addition to serving as a mounting, the frame protected the telescope when it touched the ground: while a Styrofoam crash pad on the bottom abosrbed the impact of the landing, the flywheel at the top protected the telescope when the frame toppled over on its side.

Aside from the fundamental questions of optical design and guidance, the major problem that the design faced was heating. Starting at a temperature of ~ 60 degrees Fahrenheit on the ground, the telescope was exposed to air at about 70 below zero in the stratosphere while being simultaneously subjected to the full heat of the sun. To minimize distortions the structure of tube of the telescope had thousands of small holes that allowed to disipate the heat concentrated inside the tube and also the quartz primary mirror was heavily insulated at the back and sides so that practically all the heat was absorbed and radiated at the front face. While the arrangement could not prevent changes in the focal length of the mirror, it did enable the mirror to maintain a nearly perfect surface. Since the focus of the mirror would necessarily vary, and by an unknown amount, the focal image could not always be expected to fall sharply on the film. To counteract that, was decided to allow to move the magnifying lens between the mirror and the camera, driving it steadily back and forth over the full range of anticipated variation every 20 seconds. Thus 19 out of every 20 pictures were blurred, but one was sure to be in focus. The flat secondary mirror also presented a heating problem, located as it is at the hot primary image of the sun. To ensure its proper functioning it was mounted on an arm that rotated once a second, placing the mirror in the light beam for only a 30th of a second on each cycle. The shutter of the camera was of course synchronized with the motion of the mirror.

In the improved version of the stratoscope system flown starting in 1959, this was replaced by a remote controlled TV system that allowed to correct from the ground the alignment of the mirror to maintain the focus.

Details of the balloon flight

Balloon launched on: 10/17/1957 at 8:16 cdt

Launch site: Huron Municipal Airport, South Dakota, US

Balloon launched by: General Mills Inc.

Balloon manufacturer/size/composition: Zero Pressure Balloon General Mills - 1.092.000 ft3

Flight identification number: GMI Nº 2285

End of flight (L for landing time, W for last contact, otherwise termination time): 10/17/1957 at 15:15 cdt

Balloon flight duration (F: time at float only, otherwise total flight time in d:days / h:hours or m:minutes - ): ~ 7 h

Landing site: Near Scarville, Iowa, US.

Payload weight: 1424 lbs

For this flight, the launch site was moved 250 miles west to Huron, South Dakota, fearing that if the balloon was launched from the Minneapolis area the stratospheric winds would carry it as far as Lake Michigan.

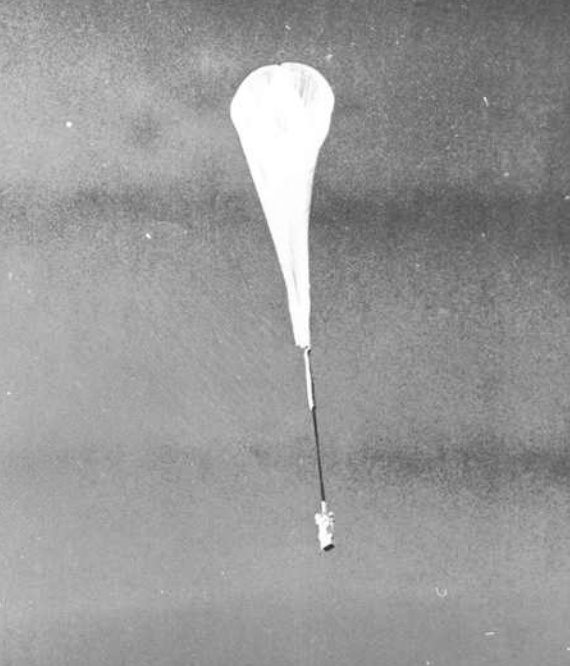

The balloon was launched by dynamic method from the Huron Municipal Airport at 8:16 CDT on October 17, 1957. After a nominal ascent it reached 83,200 feet and maintained more or less that height of flight during the following five hours. After activation of the onboard timer at 15:15 CDT the balloon separated from the payload which came to land near Scarville in northcentral Iowa. The landing was not as easy as in the previous flight of the telescope: the parachute set it down in a small clump of trees, but apparently the horizontal wind carried the parachute with the structure behind through the tree tops until everything crashed some 25 feet to the ground at the edge of the clump. The framework was seriously bent and twisted, acid from the broken batteries was spilled over the apparatus, and the primary mirror was wrenched from its cell and into the telescope tube. However, the mirror itself suffered nothing more than a few scratches in the aluminium surface.

This was the second scientific flight of the instrument and the last one of the 1957 series. For this flight the guiding mechanism was slightly altered so that during the exposures the telescope moved slowly across the limb of the solar disk. The purposes were to study the granulation there and to measure the limb darkening, that is the gradual decrease in surface brightness near the limb which is a consequence of the light coming from the higher cooler layers of the atmosphere.

Another 1,000 feet of photographs were obtaine. About 10 frames turned out to have the superior resolution which the scientists had hoped to obtain. These 10 frames exceeded the minimum goal of the entire undertaking, and contained a wealth of new information. Many other frames contained excellent portions. The photographs that included the solar limb showed it to be smooth and sharp so that, within the resolution obtained, the granulation has no affect on the appearance of the limb.

External references

- A Statistical Photometric Analysis of Granulation across the Solar Disk Astrophysical Journal Supplement, vol. 6, p.357

- An observatory at 80.000 feet Royal Astronomical Society of Canada Journal Vol. 52 Nº 1

- Balloon Astronomy Scientific American 200, 52 - 59 (1959)

- On Solar Granulation Astrophysical Journal, vol. 131, p.57

- Primary mirror used in Stratoscope I National Air and Space Museum Collection

If you consider this website interesting or useful, you can help me to keep it up and running with a small donation to cover the operational costs. Just the equivalent of the price of a cup of coffee helps a lot.