Introduction

Technology and technical advances increased exponentially the standards of security and predictability of today's scientific ballooning, transforming what was once a traditional development activity in a techno-scientific discipline permitting the production of more and better science. Much has been gained from that changes but in the process some has been lost too.

For many people who lived firsthand the strange passion for ballooning and for those whom loved this activity as an important part of their professional careers or lives, one of the things that most will miss is some sort of romanticism and adventure that were the trademark of those pioneering years.

To recover some of the spirit of that era for nowadays readers, StratoCat will begin to publish a series of articles meant to bring back to the scene those forgotten years and specially the unique and individual character of the people involved in the field in an era that would lay the foundations of the stratospheric balloon as a scientific tool.

As a first step to this goal, we present a lenghtly article entitled "Operation Stratomouse" that appeared in a medical scientific journal (Military Medicine) in September 1956. What you are about to read, is one of the most accurate and finest chronicles of the day-to-day life during a balloon launch campaign, ever written. A true tale from the old days when GPS or real time tracking from a desktop computer connected to internet were only part of the wildest dreams of science fiction. Those glorious days on which every balloon launched was an adventure itself which hardly could finish as expected.

Enjoy it. You will not be dissapointed.

(Note: Due to the poor quality of the copy of the original article we own, was not possible to include the original pictures, nevertheless some of the images that ilustrates this page were taken during the actual flights mentioned on it.)

International Falls, Minnesota, summer of 1955

The plane touched ground at International Falls, Minnesota, exactly on schedule -11:45 PM- and came to a halt in front of our brightly lit Headquarters, Einarsen's Flying Service Station. Out jumped Otto Winzen, back after launching a Navy "Skyhook" balloon from St. Paul, and with quick steps soon reached Major Simons, who was waiting to greet him. "How does the weather look for the launching tomorrow at daybreak ?" Winzen inquired. "I just heard that a cold front has been located about 50 miles to the northwest of us, but it's stationary. There's also a low pressure area building up in the southwest, in the Thief River Falls region. Let's talk to the weather people again and see if there's anything new."

Preparations for a balloon flight being an all-night affair, Winzen and Simons had soon to decide whether the crewmen should be given the go-ahead signal, or be told to call it a day. As Winzen and Simons disappeared into the darkness in the direction of the weather station, the small knots of crew-men standing in front of Headquarters gazed intently at the skies and at the "windsock" and anemometer on top the nearby hangar and volunteered their personal forecasts. The scene around them was at least that of potential action. Over to the other side of the hangar, with windows still dark, were the shiny aluminum laboratory and radio vans which had come as a caravan across country from Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, under the leadership of Major Simons. Near them one could make out the low hulks of the two Navy helium trucks. Along the runway, as though on a scrimmage line, were the Air Force C-47, the twin Beechcraft, the little Navion, the low slung Seabee amphibian, and the GI Pipers and Aeroncas some waiting to follow the ascent of the balloons once they had headed for the stratosphere, and the others standing by to take to the air in case of an emergency. Among them were assorted jaunty planes which had landed for their last refueling preparatory to heading north into the Canadian wilderness.

The men sensed that a break in the weather news was at hand when Francis Einarsen, owner of the Service Station, voluble oracle on all matters pertaining to the out-of doors, emerged from Headquarters. A square-faced, tall, muscular Icelander, with a shock of blond hair bouncing down over his eyes as he spoke, Einarsen said that the cold front near Winnipeg was beginning to move southward. Having an audience, he was soon relating how he had shot timber wolves from his Piper Cub in the Lake-of-the-Woods region the previous winter. "Had to land on the snow and pickup the wolves so that I could bring them back for the thirty-five dollar bounty," he was saying when interrupted by the arrival of Winzen and Simons.

"Doesn't look good at all," said Winzen. "The forecast is for surface winds up to 12 miles an hour at daybreak. We called St.Cloud for verification and their prediction was the same. A 15-mile gust would rip a hole in our balloon. I'd take a chance, but we won't have another balloon ready for two or three days. Let's go home and 'sackin' ".

And so another day was lost. The season was getting on, and the days favorable for flying were fast dwindling. Before our ar-rival there had been several successful flights -for the University of Wisconsin, the Atomic Energy Commission's National Argonne Laboratory, Brown University, the National Institutes of Health, and the University of Zurich, Switzerland- with the cargoes consisting of monkeys, mice, guinea pigs, Artemia (shrimp) eggs, radish seeds and corn, and cosmic ray photographic plates. Our flights were all that remained. Three were planned. The First balloon was to take aloft a full complement of mice which were to be observed throughout their lives to determine whether cosmic rays had any long range biological effect. The second was to be concerned with a short-term experiment: the mice were to be sacrificed during the first two days following the termination of the flight, and their brains studied by techniques of revealing fresh damage by cosmic rays. The third flight would be devoted to a study of an inbred species of mouse which was likely to develop leukemia if exposed to a sufficient concentration of the radiation given off by cosmic rays.

On two of these flights some carefully nurtured living cells in tissue culture would be taken along -culture from a monkey's brain, from a mouse's kidney, and from cancer tissue removed from a human being. All the cultures would be searched immediately on termination of the flight for groups of destroyed cells. Some of the cultures would then be immersed in a solution which would make them suitable for subsequent microscopic study, while the others would be kept alive through several generations and observed for genetic alterations.

To ensure safe passage for this precious cargo, a C-47 had droned its way from International Falls to Galveston to pick up Dr. Walter Hild and the cultures which he had grown in Dr. Charles Pomerat's laboratory at the University of Texas School of Medicine. Then it had proceeded to Washington, D.C. to take aboard the mice which Lt. Irwin Lebish, VC, and I had selected at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. On reaching International Falls, we found the other members of our team already on hand -Dr. Herman Yagoda, cosmic ray physicist from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda; the renowned publisher, Charles Thomas, to whom radiation problems are an avocation; and my son Dick, who was there as handyman.

These forthcoming flights were the culmination of many months of research carried on at the Holloman Air Development Center in New Mexico as part of the Air Research and Development Command medical research program. One problem had been to devise a gondola which would carry animals in the stratosphere for as long as 36 hours and bring them back alive. Whether the myriad cosmic rays penetrating the stratosphere were injurious was a question still to be settled. The Air Force wanted to know if cosmic rays presented any hazard to air crews flying on very high altitude missions, and scientists engaged in the earth-satellite program, thinking ahead to space travel, were wondering whether protection from cosmic rays needed to be included in their plans.

Conditions for launching continued unfavorable. It was always the "next day" which was to be propitious. Even when at midnight the forecast was for "marginal" weather, the gondola would be packed with animals; and inevitably around 4:00 A.M the verdict would be the same: "Let's unpack and go back to bed." There was one windless and cloudless morning perfect for getting a balloon into the air, but we remained grounded by a 150-mile-an-hour jet stream of wind at 50,000 feet, which the weather station had detected with its radar instruments. A chance might have been taken had we not remembered how last year at Saulte Sainte Marie, Michigan, one of our balloons had risen into such a stream and been sliced in half by the wind as though by a razor, with the gondola and all the rest of the gear plummeting into the inaccessible wilderness of Drummond Island, on the northern shore of Lake Huron.

To thwart the feeling of frustration which was becoming apparent in the short retorts by the men, Major Simons moved from team to team, double checking a gondola's oxygen pressure gauge here, smoothing out a personnel difficulty there, briefing continually on the requirements for keeping the animals alive on the flights to come. Although usually soft spoken and infinitely patient, he could, if occasion required, be abrupt, cajoling, rapid firing, or even categorical. He was given to banter with a serious note. "Don't forget", he remarked to one of his men who had just dropped an aneroid barometer in the bottom of a gondola, "that Murphy's law of research is particularly applicable to the gondola instrumentation: anything that can go wrong, will."

Ed Lewis, launching chief of the Winzen crew, also was continually on hand, keeping an experienced eye on what his men were doing. An ex-Navy man of habitual calm, he simply smiled at the occasional sputtering of his men. Once, after a favorable forecast had ushered in utterly impossible weather, and a crew member had remarked that "that crowd of parasitic bandits over in the weather station ought to be sent up in one of the balloons", Lewis squelched him by commenting quietly that he would be dispatching them in the wrong direction!"

"Everything's routine to Ed Lewis," one of the radiomen was heard to say. "A year ago when we were near the German-Czechoslovakian border launching a series of Winzen 'Balloons for Peace' through the Iron Curtain, I was standing next to Ed when a broadcast came through from behind the Curtain, offering a price on his head. "Cheapskates!" was his only comment. But once he did seem a little excited. That was when we were riding along one dark night to a new launch site near Czechoslovakia. Our truck, jammed with balloons and gear, had been under way quite awhile when Ed looked up at the stars and remarked to the German driver, "You're going in the wrong direction. we're headed east, not north, and are about to cross the Iron Curtain. The driver's reply was a flat "No; you're wrong" A few minutes later, after the driver had paid no heed to a further query, Ed turned off the truck's ignition, opened the door on the driver's side, pushed the surprised driver into a nose dive, switched on the key, turned the truck around. And headed back. Later, on reconnoitering the area, we found that we had been only a quarter of a mile from Czechoslovakia".

The making of a stratospheric balloon

The long waiting for favorable weather gave our team an opportunity to become better acquainted with what was going on around us. One morning we found Otto Winzen's sparkling-eyed wife, Vera, in the recesses of the hangar, checking over some balloon fabric. Sensing our curiosity, she remarked that each balloon had been designed a little differently. "We're experimenting continually. The balloons are going 35,000 feet higher than last year, and now we're looking for the design that will allow them to go still higher in the stratosphere."

All the balloons have open bottoms "appendages" was the word she used. The helium gas that takes a balloon aloft steadily expands, and if there were no way for it to escape when it has filled the balloon to capacity, the balloon would burst-like a weather balloon. To a query as to how a balloon is made, she explained that sheets of polyethylene plastic little more than one-thousandth of an inch thick -"much thinner than a lady's Chemise, yet tough as a yacht's sail"- are drawn out on a great long table at their plant in Minneapolis, and some 60 sheets are heat-welded together, with glass-fiber filaments enclosed in the seams to carry the balloon's cargo. The seams, with the filaments in them, extend upward into the dome of the balloon and all the way down the balloon to the very bottom, where they are continuous with a series of 60 nylon cords. These cords extend downward somewhat beyond the bottom of the balloon and are fastened to a forged steel D-ring. To the other side of this ring is attached the top of the silk parachute, and to the bottom of the parachute is tied a 5000-pound-test nylon rope which carries the balloon's cargo. When the balloon comes off the table it has in it some three miles of yard-wide polyethylene. Its weight comes to about 500 pounds. When stretched out on the ground, the balloon is about 250 feet long, which is equivalent to the height of a 20-story building. When fully inflated in the stratosphere, it has a diameter of about 175 feet and a capacity of over 2 million cubic feet.

"The men working on the balloon must need to be very careful not to punch a hole in the polyethylene," ventured Charles Thomas, who possesses a card-index mind accustomed to probing for details.

"Oh, we can't trust men for this job," Vera Winzen remarked blithely. "It is something only women can do. I get a little jumpy even when my husband starts handling the balloon while it's being inflated. There's something feminine about a balloon through and through, and that's why most of them are named after women." Turning in my direction, she said that it was up to me to name the balloons of the forthcoming flights.

"Fine" I replied. "I'll name them after Charles Thomas' wife, my wife, and my mother."

Meanwhile Otto Winzen had joined us and he was now pressed with questions from all sides. In his customary effortless way, his soft voice carrying a trace of guttural brought from Germany some twenty years ago, he began by saying that a balloon ascending into the stratosphere is like a rubber ball let loose in the bottom of a pool. The ball rises rapidly and on reaching the surface jumps out of the water, then falls back and floats. So it is with a balloon. It rises as fast as 1,000 feet a minute, and upon expanding to full capacity, continues upward beyond its ceiling in the stratosphere; then it discharges excess gas through its bottom, settles down quietly, and floats. If a balloon and its cargo weigh 800 pounds, about 900 pounds of helium lift will Je put into her. It is that extra 100 pounds of lift -the "free lift"- which is vented when the balloon overshoots its ceiling.

"There's something eloquent about a gigantic balloon when being launched, whether it slips away tranquilly into the unknown or goes charging forward like an enraged elephant," Winzen went on to say. "Each has a personality of its own and every one is a solo performer. From where I stand on the launch platform, I can catch from one balloon the satiny swish of a wedding gown as a breeze twists it, and from another the full resilience of a four-master after it has lurched suddenly before a gust of wind.

We've sent balloons up for many purposes, even some with rockets dangling from them which are fired into the upper stratosphere when the balloons reach 80,000 feet; but to us the flights to come have a particular significance because of their living cargoes. You'll recall the hot-air linen balloon launched by the Montgolfier brothers at Versailles in 1783 for the benefit of Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and Benjamin Franklin; how it carried a rooster, a duck and a sheep, which came out of the flight uninjured except for the rooster, whose wing was injured by a kick from the sheep just before the launching. That was the beginning of animal experimentation to determine whether high altitude flights are safe for man. A few years ago an Aerobee rocket took two monkeys and some mice very high into the stratosphere, and one of the monkeys is still alive and thriving in the Washington Zoo. But no concrete conclusions as to the effects of cosmic rays on them could be reached, because the entire trip didn't last more than ten minutes. Those animals were exposed to cosmic rays for about as long as a lion is exposed to fire as it jumps through a flaming loop. The fact that only the lion's hairs are singed doesn't mean that the flames aren't harmful. The coming flights will be the first that take animals within the range of the powerful cosmic rays for an extended time. They'll be up there near the edge of space, above 99.7 per cent of the earth's atmosphere. Let's hope that the weather settles down soon."

The problem of the cosmic rays

On another occasion we found Major Simons and Dr. Yagoda at Headquarters sitting on a well worn sofa facing the huge window that overlooks the airfield, gazing blankly at the overcast sky. They seemed to be at loose ends. It did not take long to draw them into a discussion of the cosmic rays to which our animals and tissue cultures would soon be exposed.

"I suppose you know why we're here and not back home in New Mexico carrying out these experiments," Major Simons began. "It's a question of magnetism. Our planet is a gigantic magnet, and the lines of force which connect its two poles reach far into space. The cosmic particles coming from outer space carry an electrical charge and for that reason they're deflected in the direction of the lines of force even before they enter the earth's atmosphere. Up here, in fact anywhere north of 55° latitude, the particles aren't deflected nearly as much as in New Mexico, and hence get to lower altitudes here than in New Mexico."

"But maybe I'm getting ahead of my story," the Major remarked. "Remember that the cosmic rays are not mere rays, but actual particles. You know that every atom of the earth or of the air consists of two component parts, a nucleus, with a positive charge, and a series of electrons, each negatively charged, which fly around the nucleus somewhat like the planets around the sun. By contrast, a cosmic ray particle consists only of a positively-charged nucleus. It has no electrons revolving about it. The amount of energy which a nucleus gives off owing to its speed is fantastic; it's as much as 100 billion electron volts."

"How does the energy of these particles compare with that given off by an atomic bomb?" asked Dick, trying to grasp the meaning of those figures. "A cosmic particle of iron is so powerful that it has an energy a billion times that released by a uranium atom in an exploding atomic bomb," was the answer.

The Major turned the conversation over to Dr. Yagoda by asking how far, in his estimation, the cosmic particles coming from outer space penetrate the earth's atmosphere. "Well, even up at this latitude relatively few of the heavier ones get much lower than 60,000 feet. Some gradually lose their energy, slow down and come to a halt. This kind of termination is called a "thin-down" The others are eliminated by colliding with atoms of the air. When an incoming cosmic particle collides head-on with an atmospheric atom, the result is cataclysmic: the particle and the atmospheric atom are both split into their component parts -protons, neutrons, alpha particles, and several kinds of mesons- and these go flying in every direction, giving a 'star' effect. The cosmic particle is by far the most powerful atom smasher we know".

"Now, as the fragments of the exploded atoms, the secondary rays-go sailing away," Dr. Yagoda continued, "they in turn encounter other atmospheric nuclei in their path, and further collisions occur. Tertiary rays are thus formed, and then quartanaries, and so on down to earth. By the time these byproducts reach us they're only a 'watered-down' version of what's happening up there. It's fortunate for us here on earth that the atmosphere forms a protective barrier which wards off the primary particles. In fact, the atmospheric barrier is equivalent to a jacket of lead about 40 inches thick."

At this point Dick raised another question. "Major Simons, Dr. Yagoda says that heavy nuclei get down to 60,000 feet. Why, then, isn't it enough to send the balloons to 70,000 feet?"

"Because only the lighter particles get down to that level in appreciable quantity. The "primaries" have different weights, for they consist of all the elements from hydrogen to iron. The heavier, or larger, a "primary", the better is its chance of colliding with an atom of the air. It's like shooting a barrage of bullets and cannon balls point-blank into a forest: the great majority of the bullets go further than the cannon balls before they lodge in a tree trunk. So it is with the cosmic 'primaries' A lighter particle, such as carbon, can readily penetrate the atmosphere to 60,000 feet before colliding, while an iron particle seldom gets much lower than 100,000 feet."

Now we began to understand why our balloons must reach an altitude of well beyond 100,000 feet. But we were still curious to learn to what extent cosmic particles present a hazard which man must face when he travels in the stratosphere or, our more immediate concern, what those animals resting in the laboratory van by the side of the hangar will be up against in the sky, when the first clear, windless morning takes them aloft in the gondola of a balloon.

This was one of Dr. Yagoda's favorite themes. "From studies of photographic plates taken up in balloons during the past few years, we know that as cosmic particles slow down in the earth's atmosphere they give off more and more energy. Suppose an incoming cosmic particle consists of a calcium nucleus. In the fraction of a second during which it draws to a halt, such a particle gives off some 50,000 roentgen units for every one one-thousandth of an inch of an animal's body it traverses. That's a great many units for a local area when you consider that a man will eventually die when only 600 units are applied to his entire body, in a single dose, as from an atomic bomb. If what can be seen in a cosmic ray photographic plate occurs in the brain of an animal -that is the part which, I understand, interests you most- one would expect a calcium particle during this "thin-down" to burn a very narrow furrow about a halfginch long. Under the same conditions an iron particle would be expected to leave a broader and longer path of destruction. But the damage would be along a hairline path, and there alone."

"Could you give us an estimate of how many cosmic ray thin-down paths we can expect to find in the brains of the mice that are above 115,000 feet altitude for 24 hours ?" I asked.

"My guess," replied Dr. Yagoda, "is that over that particular period of time at such an altitude, you should Find in every mouse brain about 10 paths which have been produced by the medium-sized cosmic particles as they come to a halt, and in about one animal out of three a much more prominent path plowed out by an iron particle. I don't envy you the job of locating them in the brain. I can assure you it will be like trying to find a needle in a haystack"

Readying the gondola and the radio beacon

After eight long days of waiting, we noticed from the concentric lines on the evening weather map that International Falls was between two high pressure areas, which meant that at daybreak we should have perfect launching weather. This was the signal that sent us all back to our rooms to take a nap, for the preparations are an all night affair. So much time had been lost that it was decided to send two gondolas of animals up with the balloon.

By 11:30 all the gondola crew were on hand, and the lights in the three laboratory vans were blazing. Everyone had been galvanized into activity. Upon reaching the area, we noticed that the cups of the anemometer on top of the hangar were hardly moving.

In one of the vans, interest was centered on getting the first gondola ready. Airmen John Goldsmith and Jerry Johnson were working on the upper half of the 3-foot aluminum sphere, in the top of which were the tiny instruments that were to record simultaneously on a smoked disc the temperature and the pressure in the gondola, and, powered by silver-cell batteries, were to send this information in the form of coded messages to the radio beacon on the balloon's load line, for transmission.

While Jerry Johnson was making a final check of the small cylinder which codes the messages, John Goldsmith turned his attention to the lower half of the gondola. Into it went a frame of foamed insulating plastic painstakingly cut to hold snugly each item it was to receive. Then he lowered the "cooling can" into its niche. It was a finned metal canister having a capacity of about two quarts. From it ran a metal tube which passed through the wall of the gondola to the outside. Goldsmith informed us that the canister was packed with ice which would keep the animals cool, as the gondola, in its ascent, was warmed by the sun. After the gondola had been in the stratosphere for awhile, the ice would melt and the low temperature of the water would prevent undue heat from accumulating in the gondola.

High in the stratosphere, water boils at 33°F. and the boiling, since it attracts heat given off by the animals, aids in keeping them cool. Under normal circumstances the cold is no problem because the atmosphere at that altitude is too rare to conduct much of the heat away from the gondola.

The gondola's oxygen system was then put into running order. From cylinders attached to the outside of the gondola, a flexible tube carried oxygen to a valve in the top of the gondola. The valve would open automatically when the gondola's pressure fell to a certain level. "The animals use up the oxygen," Goldsmith explained, "and that's what makes the pressure fall."

Two fans deep in the gondola's recesses were turned on, and Goldsmith showed us how one circulated the air and how the other drove the air through the long sack of soda lime -a "snake" he called it- which would absorb the carbon dioxide given off by the animals.

By 1:30 the gondola was ready to receive the mice for the longevity study. Lt. Charlie Steinmetz and Sgt. Charlie Dahlberg brought them in, exactly on time. They were in a flat wire mesh cage, each in its own compartment, gnawing away on pieces of raw potato, which would quench their thirst on the long cruise. The cage was placed on the platform which covers the lower hemisphere of the gondola. Then the two hemispheres were sealed airtight by means of 134 bolts and nuts, and around the sphere went a thick shell of insulating plastic and over that a layer of shiny aluminum foil to reflect the sun's rays. The oxygen tanks were strapped into place, and filled to capacity. The gondola purred from the vibration of its cooling fans like something alive. In another hour the second gondola was ready. It carried tissue cultures, carefully taped into place by Dr. Hild, and the mice, which were to be sacrificed soon after they had been recovered.

Over in the hangar, Vern Baumgartner, lanky, loquacious chief of the Winzen electronics crew, was keeping an eye on his men as they checked the equipment in the radio beacon, a contraption about the size of a box kite, which was to be attached to the upper part of the nylon rope hanging from the parachute. As usual, Baumgartner was warming his hands with a cup of coffee, a holdover from a habit acquired on his long watches as radio officer on destroyers in the two wars.

"At least it isn't as cold as on that New Year's Eve in 1947 when we launched a balloon from Camp Ripley, near Little Falls, Minnesota," he commented, "we called the place "Little America" because it was 40 degrees below zero. Seemed like the stratosphere had come down on us. By gosh! if a wind didn't spring up and take that first balloon right over the home of Lindbergh in Little Falls."

His cup emptied, Baumgartner set one clock in the beacon so that at 9:00 that night it would signal the ballast can near the lower end of the rope to let loose its 100 or more pounds of steel shot. Then he set another, which at 6:30 the next afternoon was to discharge the cannon straddling the rope that held the parachute to the balloon; the discharge would send a steel blade flying down the barrel of the cannon, and this would sever the rope, freeing the parachute, which would then float downward with its cargo. The beacon's radio transmitter, which was to broadcast in short wave the signals received from the gondola, was also put into running order. Now everything was ready for the journey into the Stratosphere.

The flight of the "NAN PAYNE"

It is still dark as the caravan of carts and trucks moves on to the runway. Floodlights playing on the launching site lend drama to the scene. Large red balloons are let into the air and tethered to the trucks. These indicate wind direction and wind speed, but there is no ignoring the carnival note they add. The balloon-all of its 254 feet-is soon laid down on the runway from one of the carts. Ed Lewis unpacks a parachute and ties its upper end to the harness ring of the balloon. To the bottom of the parachute he proceeds to fasten a 150 foot-long nylon rope, then walks to the other end of the rope and secures it to the bumper of a truck.

There must be a good dozen men at their stations, but Otto Winzen dominates the scene-not only in action, but also in appearance. One could not fail to spot him, his trim figure moving quickly from station to station along the nylon rope, where each man has a special duty to perform. He bends over the balloon fabric, now here, now there gently shaking its folds preparatory to inflation with helium. A skipper of a yacht of the Challenger class could not inspect a jib more carefully than does Otto Winzen his balloon. We look to see what he is wearing this time. Yes, he is dressed again in a distinctive way: white suede shoes; pale blue, floppy linen trousers; a terry cloth jersey trimmed in blue, with French tricolor weave spanning the "V" at the neckline; over the jersey, a polka dot, azure blue zippered jacket; and on his head a yachts-man's cap, blue with crossed anchors, that would have put Admiral "Bull" Halsey's headgear in the shade.

Soon Winzen is up on the launch platform, which carries a contraption that looks like a gigantic clotheswringer. The balloon fabric passes between the two rollers, over the nearest, under the farthest. Winzen gives the signal. Navyman Ledbetter turns on the valve of the helium truck, and the gas comes whistling through a huge red plastic conduit into the head end of the balloon. With a circling movement of his arm, like that of a brakeman beckoning an engineer to keep a train coming, Winzen brings life into the polyethylene. As the balloon begin to rear its head, wallowing about uncertainly, men crowd under to lend support.

More helium goes in. Then, all of a sudden -indeed, in a hash- the inflated head gives off a sonorous "whoosh !" as it rises a sheer 70 feet. The balloon appears to be pinioned at the neck by the "clotheswringer", but actually it is immobilized by the truck to which the nylon rope is attached. Still more helium goes in. There is a load of 332 pounds to be taken aloft, and the balloon fabric adds another 526-a total of 853 pounds. The scale on the launch platform weighs the lifting power of the helium that is going in. After the dial hand indicates 858 pounds, another 100 is added to take the balloon up.

The balloon is now ready. It is 5:43. The sun is just coming over the horizon and is beginning to dispel the soft blue ground haze. Winzen picks up his megaphone. This is the finale. One by one, the spokesman for each station -at the cannon, the beacon, the first gondola, the second gondola, the ballast can, and the rope's end at the truck- affirm that all is ready. Surely the balloon will spring a leak if Winzen does not let it loose soon. But Winzen is not yet ready. Leisurely he gazes into the sky to be sure no aircraft is flying in the vicinity. Turning, he steals a final glance at the balloon, which in his mind he christens the Nan Payne, and turning still more, scans Nan's brood attached along the nylon rope.

Now Winzen is ready. A quick deft sweep of his arm against release lever of the "clotheswringer", and the Nan P is set free. She rushes up through the haze like a ghostly apparition, gathering momentum as she heads toward the truck. A few seconds later the nylon rope attached to the truck is severed. Up she soars, at about 500 feet a minute, as lightly as thistledown.

6:15 A.M. The Navy radio truck with its two drivers, Bob Clark and Chief Serley, draws up in front of Einarsen's station for instructions. Winzen and Simons beckon them into an anteroom of the station where they are washing the sleep out of their eyes. As briefing for the chase begins, Simons plugs two electric razors into the wall and uses them simultaneously, one on either side of his face, completely oblivious to their hum. One, he explains, is his spare, so why should he not keep it in good running order. Winzen recommends Grand Forks, North Dakota, as the site of the first rendezvous for the truck and the planes. From his image in the mirror, the men manage to learn that Major Simons concurs. En route, first at Baudette, Minnesota, the drivers are to get bearings on the balloon and transmit them to the radio station in the van standing near the hangar. Soon the truck is off down the road with dignity and dispatch, its antennae bending in the wind and the direction finder pointing west.

6:40 A.M. The Navion, piloted by the veteran Russ Iverson, takes off to keep its eye on Nan P. Since her departure, Nan P has been heading southeast, blown by the prevailing surface winds.

7:30 A.M. Russ reports her over Black Duck Lake at 110,000 feet. Having gotten into the stratosphere, she is turning back toward International Falls.

8:30 A.M. Now she is heading due west. At this time of the year the winds up there are always toward the west. Short-wave radio messages from the balloon's beacon are coming in to Joel Baumgartner in the radio van every ten minutes. I hear the insistent, twanging "dit da da's" and inquire what they mean. "That's 'WEH' coming in now; means that she's at 115.000 feet," he replies. A little startling, hearing one's own initials called down from the heavens!

9:15 A.M. The telephone in the hanger rings. I answer. The voice says: "This is the CAA Office in Minneapolis; thought Simons and Winzen would be interested in knowing that a flying saucer has just been reported over Little Fork."

10:30 A.M. Through the theodolite (a surveying instrument for measuring vertical [elevation] and horizontal [azimuth] angles by means of a telescope), Sgt. Jack Conift has been keeping continual tab on the balloon, she is now 80 miles to the west, and perched up there at 118,000 feet. The sergeant has the temerity to call this magnificent pearl an "onion," but no protest comes from his audience because he is speaking merely of her shape. He adds that she is "tighter'n a bullfighter's pants," and should be belching off some gas soon.

"How far do you think the balloon will go ?" I ask.

"Oh, she'll just keep ying-yanging until she gets near Montana," was his prophetic reply.

11:30 A.M. The Navion advises that the balloon is near the southern shore of Lake-of-the-Woods, moving along at about 24 miles an hour. Her short-wave signals give the following message: altitude 118,000 feet, gondola temperature 73ºF, gondola pressure 15 pounds per square inch.

1:00 P.M. Now that the Nan P is well on her way to the west it is time for the C-47 to join the Navy truck and the Navion in the chase. The C-47 will get under her, obtain bearings through its astrodome, and keep in range until nightfall in order to make further checks on her position and speed. We prepare to board the plane. Dr. Hild packs his microscope and other equipment into the fuselage, and Lt. Lebish, the "control" mice, which are to be exposed to much the same rigors of travel as the mice which have been bome aloft. Major Simons and I are the last to climb in. At 1:37 we are leaving the runway and are soon over dense, lake-dotted forests. In a half hour we have caught up with the Nan P, and stay with her for awhile.

4:50 P.M. We land at Grand Forks, North Dakota. Having located the balloon to the east through the theodolite, we hail a taxi and go into town to find a restaurant. We had heard of Major Simons' Diamond-]im-Brady appetite and wonder whether there has not been some exaggeration. When the waitress turns his way, he does not give her a chance to ask for his order. "Bring me a quart of milk with two glasses of iced tea and a double hamburger steak dinner without the peas and potatoes on one of them," he says. And when the waitress, baffled, looks around to see who else he is ordering for, he continues, impatiently, "It's for me; bring 'em all at once, and if they're not ready, bring me the pie with two scoops of ice cream instead of one, and I'll start on that-and, oh yes! bring the soup, too, I'm hungry." When she asks, "What kind of pie?" he replies, "it doesn't matter, just bring it - well, make it cherry pie." It was not long before I heard tittering from the waitresses who had gathered in a huddle behind us to learn the latest about one of the customers. "Bet he'd even go for a steak a'la mode," I heard one of them say.

8:45 P.M. We have returned to the airport. The Navion is now moored near our C-47. The Nan P is far to the west, sailing resolutely into the fading sunset. Brilliantly lighted by the setting sun, she looks like the evening star. A little later, having taken on a harvest moon hue, she is outshone by Venus. A pity that she is expendable! Tomorrow, after she has accomplished her noble mission, a segment of her wall will be ripped out by a line attached to the top of the falling parachute, and she will wallow and sink, like a harpooned whale, and ultimately be found in farmers' refrigerators, reduced to vegetable bags.

8:50 P.M. The Navion, which took off a half-hour ago, reports that the balloon is over Devil's Lake, at 115.000 feet, and traveling at 39 miles an hour. I inquire: "Why 39 miles? Why not 40?" and am told curtly, "Because it's 39." Who was it, I ask myself, who so aptly remarked that "the Open mouth is the source of all annoyance"? By 9:10 the Nan P has dropped to 100,000 feet. Major Simons appears worried; he wonders why she has not yet dropped her ballast.

9:30 P.M. Our C-47 takes off, and Grand Forks is soon far behind. It is too dark for us to see the Nan P, but her radio signals tell us that she has climbed back to 120,000 feet. We continue west, and being thoroughly worn by the vibration of our old "gooney bird" -as the C-47 is called- we scan the map in search for the nearest field.

11:15 P.M. At an Air Defense Command field in the middle of North Dakota we taxi to a stop. As the door of our plane opens, we are confronted by an officer and an armed guard. The officer inquires of Major Simons the nature of his mission, and is given an explanation. He then introduces himself as Lt. Edward Fox, Officer of the Day, and in the name of the Commanding Colonel, offers us quarters for the night. As we walk toward "Operations," Fox remarks: "We're certainly relieved to have that mystery cleared up. At 5:30 this afternoon we received a call from the FBI at Grafton that a 'flying saucer' had been spotted. A farmer had called the sheriff, stating that he had seen a strange light moving slowly through the sky, and the sheriff had communicated the news to the FBI. In three minutes we had a scramble in the air".

"A what ?" Lebish inquires.

"A scramble," the Lieutenant answers. "Three interceptor 84's. Those jets were under the 'saucer' in five minutes, and no matter how high they climbed they still had to look up to see it."

"How high did they get," Lebish asks. "Oh, about 40,000 feet, maybe," he parries.

4:20 A.M. Fortified with a substantial breakfast, we are in the air again, following the Navian up. I wonder how easy it will be to find the balloon up there in that dark immensity against the background of the stars, and am reassured by Major Simons' remark that the balloon is easier to see in the moonlight than at early dawn. The snores around me reveal that the men are abiding by the catch-as-catch-can rule. But after a half hour all are on the alert.

5:48 A.M. The Nan P is discovered far, far ahead, reflecting the silver of the nearby moon. Major Simons' plotting of her course all yesterday afternoon and evening has led us directly to her, The Navion is circling under her as we arrive. In the interim the balloon has travelled 129 miles at an average of 16 miles per hour. She has slowed down as though waiting for us.

6:25 A.M. Now a new angle. Both we and the Navion are circling downward to have a rendezvous with the Navy radio truck which, we hear by radio, has reached the scene during the night. The plan is that on the last lap, Simons, Hild, Lebish and I are to join the truck crew in tracking down the quarry.

7:00 A.M. We put down at Minot, North Dakota. C-47, Navion and the truck confer. The tracking center at International Falls is then consulted by radio. Not long afterward six of us, including the two drivers, head west in the truck. Three ride on the front seat and the other more fortunate three are stretched out on the floor. For hours we keep 15 to 20 miles ahead of the balloon, taking bearings on her, and radioing her position back to Headquarters at International Falls. By midafternoon we draw into Alexander, North Dakota.

5:00 P.M. Continuing westward, we reach Montana. The balloon has been moving more slowly than anticipated, and zero hour is approaching. It is obvious that we have come too far west. Someone remarks that ballooning offers more opportunity for hindsight than any other diversion. Doubling back east a full ten miles, we come to a cemetery perched on a hill, and one of the drivers volunteers that cemeteries are where balloons like to land. "There's something behind that superstition," remarks Hild, "I can recall from school days back in Kid the story of the balloon launched during the festivities at Napoleon's coronation, how it drifted down to Italy and finally crashed on Nero's tomb."

At the driver's insistence, we decide to reconnoitre the sky from the sister hill across from the cemetery. We unfasten the rickety gate at the base of the hill, drive in along parallel indentations which we refer to euphemistically as a road, get to the top, and step out of the truck gingerly, for we find that this has been a favorite idling spot for cows. Major Simons changes clothes and shoes, metamorphosing into a lumberjack. A second pair of socks is put on by Lt. Lebish in readiness for a dash through cockleburr laden wheat fields. Dr. Hild adjusts a telescopic lens on his camera. Chief Serley, one of the drivers, puts on a red baseball cap, which matches the color of the luminescent cloth thrown over the top of the truck to attract the attention of the C-47 and the Navion.

The Major is soon flat on his back, searching the sky with binoculars. Heavy battle-ship-gray clouds, with only an occasional peephole, have suddenly gathered. The C-47 advises Bob Clark, sitting at the radio in the truck, that it cannot see the balloon; it has ascended to 14,000 feet but is unable to get above the clouds.

6:15 P.M. Major Simons cries out, "The gondolas have just been cut down... now having a free fall ... parachute's not opening up yet ... they've fallen at least 25,000 feet and are stili plummeting ... ah! now the parachute's opening ... the gondolas are swinging back and forth under the parachute like they're on a flying trapeze... now I've lost them behind the clouds." Turning his binoculars back to the balloon, he tells us that a big slab has been ripped from her side and that she is keeling over on her side and crumpling.

Back on his feet again and heading quickly for the truck, the Major announces that we are a mile or two to the west of the "cut-down," and should be 25 to 30 miles to the east. "Get us out of this pasture fast, will you?" he says to Serley, "and then barrel her down the road. We're already a half hour late. The 'load' should hit the ground in another 35 minutes." Heavy dust is siphoned on to those of us who are in the back of the truck. After some 15 minutes had gone by, the brakes screech and our truck comes to a halt. Major Simons mounts to the roof of the truck, and someone comments that he is up there in order to get closer to the sky with his telescope. Passing motorists wonder what is happening in the sky or to us.

On we speed again. My wristwatch keeps ticking away until the 35 minutes are up. No one says anything now. There is nothing else to do but to pull into the nearest town. Garrison, at the North Dakota border, is where we come to a halt. We park the car on the curbless main street, and the Major goes into a filling station and telephones our location to Headquarters at International Falls. Not long afterward we hear a nearby radio station interrupt its program to tell all persons in the area to be on a lookout for our g-ondola and parachute. They are told a sign on the gondola indicates the telephone number at International Falls that should be called, collect.

Over the radio we hear that the C-47 and the Navion have begun to comb the area, the C-47 at 200 feet, the Navion at hedgehop level. They are looking for congregations of cows, who are curious about gondolas, and for a line-up of cars along a road, for farmers, too, take advantage of extraordinary diversions such as this, The C-47 reports seeing a scramble of jet planes hedge-hopping just a few miles off, but the crew are too fatigued to realize that the jets had been dispatched from a nearby Air Defense Command field to investigate the two silver orbs which had been seen floating down from the sky.

7:15 P.M. We are all in a dingy bar at the edge of town with the truck pulled up at the door so that we can hear its radio. All order hamburgers and coffee except Major Simons, who asks for soup to begin with. Our orders are placed beforc us, and as someone is making a comment about the sign, "TRADE, TREAT OR TRAVEL," which hangs on the mirror behind the bartender, the radio in the truck starts up. It is the C-47 reporting that the gondola has been located in such-and-such an area. Out we swing like firemen starting for a fire, each clutching his hamburger, except for the Major, who casts a frustrated look at his plate of soup as he stops to pay the bills. Soan we are off Bob Clark pushes the car's throttle so far down that we fear his foot will go all the way though into the carburetor. Major Simons, in his customarily jovial way, makes some wisecrack about the plate of soup he left stranded at Garrison. After we had torn along a good 20 minutes through country with farm houses miles apart, the Navion contacts us.

"We've just seen her; 'tain't nothin' but the torn-up balloon."

So we settle down by the side of the road and wait. Against the rapidly darkening eastern sky we see the C-47 and the Navion head back toward Minot, defeated. The redpurple sunset holds no charm for us.

7:45 P.M. The word comes from International Falls exactly two hours after the cut-down. Mrs. Jan Cammermyer has the "package" on her farm. It is one mile west of Alexander, the town we had passed through that afternoon. That is at least 20 miles away, and we estimate that there is only thirty minutes of oxygen left. Following instructions implicitly, we finally reach a line of cars parked on the side of the otherwise empty road. A farmer at an opened gate points at the crowd in the middle of a cornfield, and in we go.

We start on one of the gondolas. The farmers pitch in and help. Four of us remove, as quickly as we can, the 134 bolts which seal its upper and lower halves. We raise the lid and discover life inside. While one of us places the mice (90 of the 93 are still living) in more comfortable quarters, the others remove the insulating jacket of the second gondola. The gondola is icy cold. There is not much need to remove those 134 bolts rapidly, but we do so anyway. The farmers are asked to send their children for a pail of water, so that they will not be there when the gondola is opened. The conditions inside the gondola are as anticipated. Even Dr. Hild's tissue cultures all 40 of them are frozen solid. Hild -a buffalo-chested and bull-necked, with a deadpan expression concealing a sharp wit- picks up one of the cultures, turns a flashlight on it, examines it with a practised eye, then replaces it without so much as curling his lips. He has had disappointments before. His long experience as torpedoman on a German PT during the war had taught him to accept situations as he found them.

It is useless to examine further the mice in the second gondola, but the 3 dead ones in the first gondola need to be autopsied in an effort to learn why they died. Lt. Lebish and I carry them into the back of the truck, and with the aid of a flashlight soon have the job completed. No apparent cause of death is found. The brain and spleen and other organs are preserved for later study under the microscope.

10:10 P.M. We are off in the truck headed for Alexander to get something to eat. Reaching the outskirts of the town, we come to a halt in front of a dusty old cafe, to which we have been attracted by the neon sign, "STEAKS." The strains of "Fine and Dandy," played with some unusual improvisations, greet us as we push open the swinging doors and walk past the bar.

"That isn't the way I feel," says Lt. Lebish as we find our way to a cubicle. A Mona-Lisa smile spreads over his face as he saunters toward the piano, calling back, "Order a steak for me." A word with the pianist, and Lebish seats himself before the keyboard. The clink of china ceases and groups of men at the bar pause at their beers and whiskeys, as Lebish, a professional jazz pianist in New York prior to entering the Army, lets loose on a wide-open boogiewoogie, the "C Jam Blues," his head beating the cadence. That left hand of his is putting into the theme all the hullabaloo of the chase we have just experienced. The silence continues as he launches into another tune, then another, winding up with the soft, sweet and blue, "One for My Baby, and One More for the Road."

11:30 P.M. We are now ready for the long drive to Minot, which is a full 150 miles to the east. Upon reaching the truck, we find that one of the tires is flat. It is midnight before the truck is fit again to travel. Simons, Hild and Lebish curl up in the back of the truck and go to sleep. Where they have found room between the gondolas and the other equipment is hard to conceive. The two drivers and I are in the front seat. One of them, Chief Serley, has the wheel. After an hour of piercing the pitch-black night, the truck begins to weave back and forth across the road. Responding to my casual comment on the pecularities of his tactics, Serley explains that he is trying to avoid the ruts. This happens again, and gradually the truck heads straight for a ditch at the side of the road. I shout; the other driver, Bob, who is next to Serley, wakes up, and catches the wheel just in time. Serley halts the truck, candidly admits that he had been asleep at the wheel, and without further ado, steps out of the truck, walks around the front to the other side, and I slide over to the middle of the seat as he gets in and promptly falls asleep. Bob is now at the wheel. A thunderstorm breaks loose, and soon the truck is slithering back and forth as though it were negotiating a wet Georgia clay road. After twenty minutes, Bob tells me that he, too, is finished. Following Serley's example, he soon is on the far side of the seat, asleep, with me now at the wheel. Chauffering those five bodies makes me feel like an ambulance driver, if not an undertaker. The soft rear tires and the heavy load make driving precarious. The roughness of the road is such that the truck rattles like a bucket of bolts, outdoing the thunder. We arrive at the Minot Airfield, unload on to the C-47: proceed to town, and as we enter the hotel for a "night's" sleep, the day is breaking.

Late that afternoon we are back at our base, in International Falls.

The flights of the "EVELYN ANDERSON" and "EMMA VOGELGESANG"

That evening, with a spell of good weather assured, the plan for the remaining two flights was set. The Evelyn A was to be sent up at daybreak, and the Emma V the following morning. The Evelyn A, with a full load of mice for autopsy during the first two days after their recovery and some trays of tissue cultures for study on location and later in Galveston, was to be cut down after a 26-hour run. and the Emma V was to have a 10 hour flight, carrying the mice susceptible to leukemia.

By daybreak the hulk of diaphanous polyethylene had been laid out on the runway. From the back-and-forth bobbing of the red weather balloons at 100 and 200 feet it was apparent that the winds were "marginal" for launching.

Soon the Evelyn's top, inflated and erect, was weaving back and forth in the wind, awaiting only Otto Winzen's signal to let her be airborne. As the familiar megaphone was slowly and deliberately coming up to Winzen's lips, Major Simons, standing next to the gondola, began waving frantically. A final pressure check had disclosed a leak in the gondola. A truck was soon speeding to the hangar to fetch the acetylene torch and tools, and during the ten minutes that elapsed, gusts of wind indented and swirled the Evelyn A. Her protests, expressed as satiny swishes, were becoming louder as, the job completed, the megaphone came once more into position. Although the launch platform, weighing 5,500 pounds, was jumping off the ground with every upward tug of the balloon, Winzen took time to scan the heavens. It looked as though, in the manner of the Indians of the Plains, he were sending up a silent prayer.

"All set now? Watch the rope," he cautioned through the megaphone. Then he turned, nimbly unlatched the launch arm, and the Evelyn A leaped skyward, giving off an agonizing, crashing, echoing sound. As she moved swiftly in the direction of the truck, a gust of wind caused her to hesitate; her long nylon rope then lashed out to one side in an undulating movement as though it were a whip being cracked. Agile little Herk Ballman, standing at the level of the beacon, just managed to jump out of its way. An old hand at balloon launching, he had always been successful at outwitting a rampaging balloon. His close call brought to mind a launching in Europe in which one crewman had had his scalp ripped from one end to the other by a rising gondola, and another his forearm mangled and his shoulder dislocated by a swerving nylon rope which had momentarily looped itself around his arm.

Gathering momentum, the Evelyn A, circling like a twister in a tornado, scooped her "packages" off the ground, and was about to dash away with the wind when, with a horrendous, resounding crack, which shook the air like an explosion, she was halted by the tautened rope which still remained secured to the truck. It seemed that she was beginning to pul! the truck skyward. Ed Lewis, customarily stationed at the truck to perform the last rites, was trying frantically to sever the rope. In watching the balloon's antics he had got his knife turned around and was sawing away with the wrong edge. A second later the Evelyn A was cut free.

The hours passed, and the Evelyn A had not gone very far. By noon she could still be seen through the theodolite, at 131,500 feet (about 25 miles), a new world record altitude. In her native element, she was now as poised as though sitting on a roost.

At daybreak the next morning we were by the side of the road, 20 miles east of Baudette, Minnesota, keeping track of the Evelyn A through the theodolite. Never before was a balloon so high after a night's flight. It was evident that the beacon had let loose its 175 pounds of ballast during the night, allowing the balloon to bounce back to its record altitude. The cargo now had added meaning.

A little after 7:00 we caught a glimpse of the opened parachute. At 7:40 the message came that the gondola had fallen in an impenetrable wooded bog. Soon afterward we heard that Major Simons, taking a calculated risk, had landed an Aeronca on a plot of high grass two miles from the scene and was beginning a trek across a treacherous bog. A helicopter had been dispatched from Duluth.

Upon our return to International Falls at 11:00, Einarsen's Seabee, with Vera Winzen and Sgt. Dahlberg as observers, was landing on the runway after reconnoitering the site where the parachute had brought the gondola to earth.

"The gondola's in a bog twenty miles this side of Pine Island," Einarsen exclaimed. "On hedge-hopping over the area, we found the underbrush so thick that even a jack rabbit would lose its way trying to get through. Some distance away we spotted a footpath, but it seemed to end in the top of a spruce tree. Wasn't any place to land -too many cat-faced, cowhorned cedars and arsenic-green sloughs- so we went over to guide Major Simons to the gondola. It looked as though every step took him knee deep into the soggy moss. Once, after circling, we saw him, face down, over some moldy tree trunks and roots, apparently drinking some of the black water that was lapping the roots. Looks like a one-way trip to me. Gas was getting low, so we had to leave."

By noon, three of us were over the area in the helicopter, a Sikorsky H-5. The terrain below was as rugged as it had been sketched by Einarsen. A column of smoke spiraling into the sky led us directly to Major Simons. Only 200 yards separated him from the gondola, which he was unable to see. Fortunately the gondola was in the shade, but was any oxygen left in its tanks?

The 'copter was lowered to treetop level -some 35 feet from the ground- and hovered there while the pilot, Lt. Forbey, put the winch into action. Lt. Flatter, selected for his litheness, got into the harness at the end of the cable, and was soon swinging in mid-air. Then a gust of wind hit the 'copter, engaging its tail in a tree top. The 'copter lurched, then righted itself again, but not before its rear rotor had clipped off the topmost branches. The way clear, Lt. Flatter was quickly lowered to the ground. Just as soon as he had slipped the cable's hook under the harness of the gondola, the winch again went into action, and shortly the gondola was aboard. Without further ado, our whirlibird was off.

Another 20 minutes found us on the stubbled landing strip of the game preserve on Pine Island, and the gondola, the autopsy equipment and I unloaded. One of the rotor blades was rather deeply indented by the impact. The rescue of Major Simons and Lt. Flatter was uppermost in Lt. Forbey's mind as he raised the 'copter in the air to test its navigability. Satisfied, he threw open the controls, and with the clatter of an eggbeater, the 'copter was off.

A game warden was on hand with his truck. and in a few minutes we reached the clearing in front of his cabin. Finally the gondola was opened. There they were, all 60 mice cocking their eyes at the warden and me as though asking for food. The tissue cultures, too, were unscathed.

At 2:30 that afternoon, Abe Abramson, Dr. Hild and Lt. Lebish drove up in the radio truck, covered with dust thrown up from the almost forgotten lumberman's road they had managed to find. I was surprised to see them. Abe's chief concern was for the Emma V, launched that morning at day break. He pointed her out to me. There she was, high in the sky, very high. But Lebish's eyes sought out the mice, and Hild's thoughts were on his cultures. Upon seeing the cultures unharmed, Hild did not so much as crack a smile. He proceeded simply to gather them together and take them into the ranger's cabin. For an hour after that we could hear his Zeiss camera clicking as he found cells of particular interest under the microscope.

The Emma V was chattering volubly on the truck's radio every ten seconds, as saucy and repetitious as a parrot. Her gondola was to be cut down automatically at 4:00. Precisely at 4:00 the radio in our truck blared, "She's been cut down" -the C-47 was talking- but we were looking straight at her and we knew this was not true. Through the theodolite, we could plainly see the gossamer-like thread with two or three molecule-sized glistening objects hanging from her bottom. The minutes passed, and the Emma V was still holding on to her load. An hour passed, and another, and she remained obstinate. This had never happened before.

That night and the next day went by, and still the Emma V clung to her gondola of mice. Hope for the animals had faded. At intervals during the day we painlessly sacrificed the mice which had been recovered from the Evelyn A flight, preserving the brains for later study. It was necessary to obtain the brains at this early stage, for any nerve cells which may have been killed by cosmic rays would be expected, in time, 10 vanish without trace.

Camp at International Falls broken, except for two airmen who remained to keep a watch on the Emma V, the C-47 took us back to Washington. By 4:00 the next morning the 90 mice from the Nan P, apparently none the worse for their experience, were back in their cages at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. The 100 "control" mice which had taken the journey to International Falls and back without being sent into the stratosphere were placed in cages on an adjoining rack. Will the two groups live equally long? 'Will the litters they bear be equally numerous and healthy? These are some of the questions which only time can answer. As to the brains now preserved in bottles, will the paths of cell destruction predicted by Dr. Yagoda be found? Helping us to answer this last question are Dr. Norbert Schummelfeder of Bonn, Germany, and Dr. Erik Krogh of Aarhus, Denmark, who have had long experience in the techniques needed for this particular work.

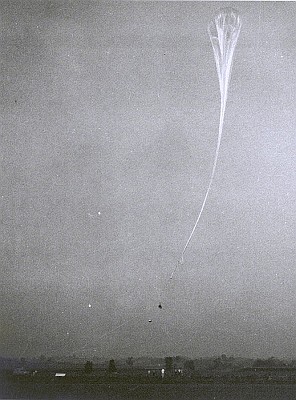

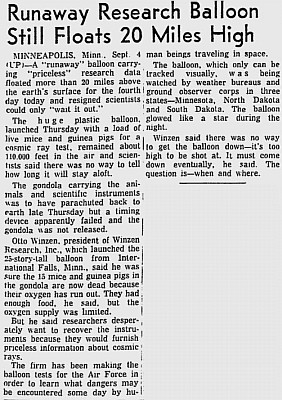

At home over coffee a few hours after my return to Washington, my eyes lit on an item in the newspaper which had to do with an errant balloon over Lake Superior. Our Emma V was described as an unruly giant. The following morning the account was continued, the caption reading, "Balloon Dips But Evades Plane Guns," and in small print, "A huge runaway research balloon, aloft at the edge of space for four days, tantalized scientists today by descending to an altitude just out of range of airplane guns. An Air Force jet stood by at Duluth, Minnesota, ready to go after the balloon the moment it descended to 40,000 feet, the plane's maximal altitude." On the fifth morning there was this surprising announcement: "Wandering Balloon is First Satellite," The Emma V was sighted over Bathhurst, New Brunswick, and was headed over the Atlantic for "a high-altitude European tour." Otto Winzen was quoted as saying that some of his balloons have wound up in Norway, and one even in North Africa.

In spite of the misadventures on our expedition, the carrying of animals very high into the stratosphere has now become an epic reality, largely through the ingenuity of Major Simons and Mr. Winzen and their skilled and colorful teams. Clear-cut answers as to whether cosmic rays are hazardous are bound, in time, to emerge. Up there, in the as yet hostile and forbidding fringes of space, where it is always night, the ubiquitous mouse has gained a foothold. Before man can do likewise, or, indeed, pierce the stratosphere and travel through the black unknown beyond, he will continue to need balloon-borne animals as forerunners-unless, per chance, man himself is willing to serve as "guinea pig" for his fellowman.

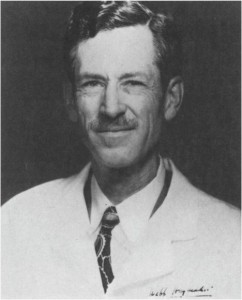

About the author

Dr. Webb Haymaker was born in Washington, DC on June 5, 1902. He attended the Medical College of South Carolina studied at the University of Wurzburg and University of Vienna and upon return to the United States received his M.D. degree in 1928.

His postgraduate education took him to the Pennsylvania Hospital, as a resident in Pathology and also his insatiable appetite for travel and new ideas took him to France, to the American Hospital in Paris and at the Institute du Cancer. A few years after during a short stay in Canada he met Evelyn Anderson, a PhD biochemist, whom he married in 1936 returning to Europe again. Back in USA he became Assistant Clinical Professor of Neurology and Lecturer in Neuroanatomy at the University of California School of Medicine.

After US involvement in the World War II, he was commissioned in the Army and assigned to the Army Institute of Pathology in Washington, D.C. where he rose to the rank of Lt. Col. When released from active duty he served as Chief of Neuropathology at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) until 1961 when he assumed a research position in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), at Moffett Field, California where he remained until his death.

Webb Haymaker was one of the best known and respected neuropathologists in the world. He was one of the first to be certified by the American Board of Pathology in Neuropathology and he was influential in making neuropathology a recognized subspecialty of pathology in the United States. He was also prolific writer, traveler and lecturer. Of his many publications perhaps the best known is: "The Founders of Neurology" (Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL, 1953) which is still popular today. One of his major interests in research was on the effects of ionizing radiation on the nervous system including x-rays, protons and cosmic rays which he pursued during the last twenty years of his life at NASA. Webb was famous for his marvelous sense of humor which is illustrated in the "Operation Stratomouse" chronicle that you had just readed.

He continued working until shortly before his death, which occured of complications of preleukemia on August 5, 1984.

(Resumed from the obituary by Kenneth M. Earle published by Springerlink in Acta Neuropathologica Volume 66, Number 1, 1985)